What is a Neural Network? No maths explanation

Disclaimer: This blog post is heavily inspired by 3Blue1Brown’s video here. Please check it out! It is a really amazing and educational channel

Disclaimer 2: This is intentionally a very simplistic explanation of what a Neural Network is. The intention of this blog post is to shade some light on the concept of Neural Network only, not to provide technical details on how to implement one

Hidden layers, linear algebra, calculus, feedforward, backpropagation… the first time you read about Neural Networks, the amount of terms and math most articles and books spit out can be overwhelming . While it is necessary to fully understand these concepts if you want to work with Neural Networks, they can be abstracted when first introduced to the concept.

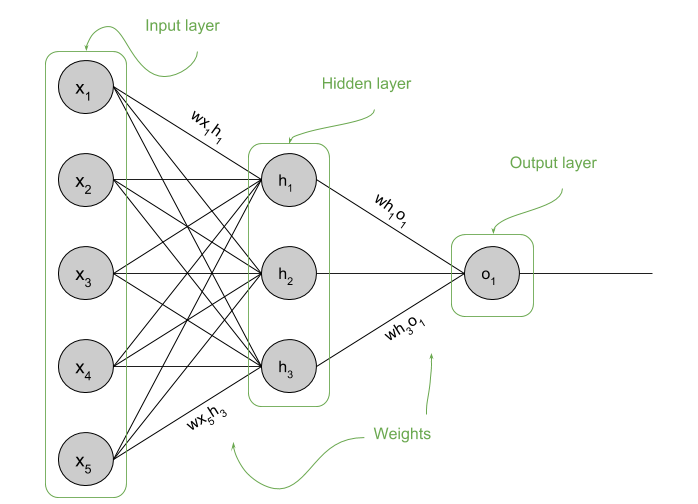

In this blog post I am going to explain what is a Neural Network and how it works. For that, I will take the simplest model for clarity. That is a fully connected Neural Network with one hidden layer and one output layer. Fully connected just means that every node in a layer is connected to every other node in the next layer, bare with me.

Structure of a Neural Network

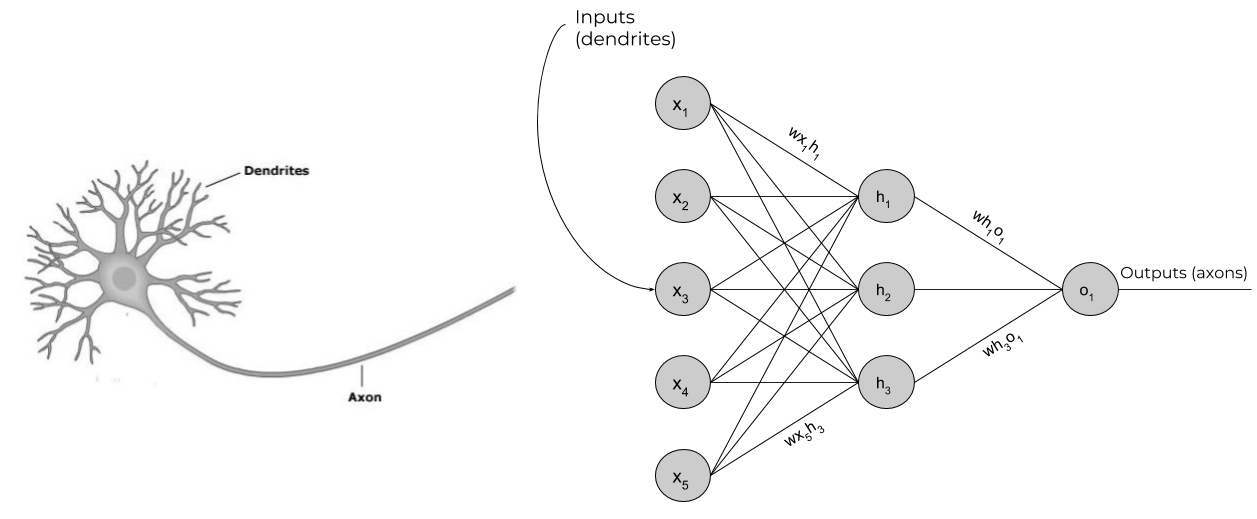

A Neural Network, much like Logistic Regression, is a way of modeling a function that fits our data. In this case a (very) complicated non linear function with (usually) thousands of parameters. A typical fully connected Neural Network consists on an input layer, one or more hidden layers and an output layer. Each node in a hidden layer is called an activation unit or neuron. In a fully connected Neural Network, each neuron in a layer is connected to each neuron in the next layer by some weights. Those weight indicate how much a neuron influences the neuron is connected to. A big weight will make the connected neuron to have a greater value, which will make that neuron to have a greater value as well, and so on.

Please note I’m skipping the concept of bias for clarity. I believe that, though being an important part of the network parameters, it can be skipped in an introduction to the topic.

The number of neurons in the input layer is equal to the number of features that each sample in our dataset is composed of.

Imagine that our network wants to predict the price of a house. To do so we get a dataset with samples consisting on 5 house features and a price. These 5 features, properly preprocessed and converted into numbers, are going to be the input of our network, while the price is going to be the expected result, or ground truth.

Since each unit in a layer affects each unit in the consecutive layer, if we have

one hidden layer with 3 neurons and an output layer, that makes already a network with 18 parameters

to tune: 5*3 for the input layer to hidden layer + 3*1 for the hidden layer to the

output layer.

That may sound very few parameters, but this was just a very simple and illustrative example. The classical example when studying Neural Network is the MNIST dataset of handwritten digits. Each digit is represented as a 28x28 pixels image in grayscale. When unfolding the image to input it to a network, it is converted to a vector of 28*28 = 784 input features. As you can see things escalate quickly. And this is only for 28x28 pixel images!

This exponential growth of parameters makes Neural Networks computationally very expensive, and this is why until recent years they’ve been mostly an academic research topic.

Training a Neural Network

In order to train a Neural Network, we will pass every input sample through all the layers in the Network, calculating the dot product of the input by the weights connecting it to the hidden layer, and passing the result to the next layer. This is called forward pass. Once we arrive to the output layer, we will calculate the prediction error comparing our result with the true value. We know that value because is part of our dataset. In our particular example would be the price of the house.

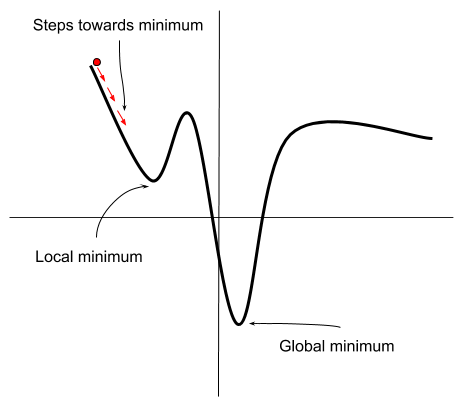

This error will then be used to adjust the weights on all the layers, so that it is minimized. To minimize the error we can use an algorithm like gradient descent. Gradient descent and other algorithms takes as input all the samples and a variable called the learning rate. This variable describes the size of the step we take towards the minimum of the function we’re trying to fit. This is very important and requires a bit of tuning for each problem: If you take too small of a step, the algorithm will be very slow and can get trapped in what we call a local minimum:

If you take too big steps on the other hand, you may overshoot the global minumum. One needs to find the balance via experimentation.

The process of propagating the error back to all the layers is called… well, backpropagation.

Mathematically, backpropagation can be a bit tricky to understand if you (like me) are not used to calculus. However, the concept of what it is doing is fairly easy to understand: During backpropagation, we’re going to propagate the calculated error back through all the layers. This is done in such a way that the neurons that were farther from the true value will be multiplied by a greater factor than those that were closer to the true value.

We will repeat this process a number of times (epochs) until we obtain an acceptable accuracy. We need to be careful as always to not overfit by training too many epochs. For that, we will use a subset of the dataset that we’ll call validation set, and make sure its accuracy goes in pair with the accuracy of the training set.

Making predictions

Once the network is trained, in order to make a prediction we only need to perform

a forward pass and get the result from the output layer. If the result is a continuous

value, like the one in our example (remember, house prices), the output is already

what we want. If instead we’re on a classification problem (for example disease prediction), then the output of the

network is not exactly what we want. The output in this case will be the probability

of the input sample to belong to the positive class. This is a number between 0 and 1.

Thus we need a threshold function to determine if we classify it as positive or not.

A usual threshold is 0.5, though it depends on the problem in hand:

- If output >= 0.5 then we classify as diseased

- If output < 0.5 then we classify as not diseased

Final notes

The number of hidden layers, units per hidden layer, learning rate and many other choices are hyperparameters of a Neural Network. To find the best hyperparameter values for your problem, you must investigate by modifying them and training your network until you get results you’re happy with. Unfortunately there are no rules for how to initially define those parameters other than intuition and experience. It is for all these reasons that training a Neural Network is computationally hard.

I hope this post was useful and you have a slightly clearer idea of what a Neural

Network really does. If you are interested in knowing more technical details, let me

know in the comments and I may write a complete, step by step implementation with

explanations ![]() , share!

, share!

Cheers!